| Publication Details: | |

|---|---|

| Publication: | “PC Plus”, UK |

| Issue: | 92 |

| Date: | May 1994 |

| Product Information: | AutoCAD LT for Windows |

|---|---|

| Price at time of publication: | £495 |

| Supplier: | Autodesk Limited |

| Phone: | 01483 303322 |

| Fact Panel: | |

|---|---|

| Display Types: | Windows |

| Minimum Requirements: | 386; 387 Maths Co-processor; HD (8Mb free + 8Mb min. Permanent Swapfile); 4Mb RAM; Mouse |

| Available on: | Dual-Media (3 1/2″ 1.44Mb & 5 1/4″ 1.2Mb) |

| Other Hardware: | Printer / Plotter |

Feature Review: AutoCAD LT for Windows

Autodesk have set the Mid-Price CAD market alight with a new low-cost version of the Crown King of desktop CAD – AutoCAD LT. TIM BATY assesses one of the first production copies.

Ever since Autodesk’s AutoCAD persuaded everyone that Computer-Aided Design (CAD) was viable on the IBM PC, competitors have developed programs with similar features, but at lower prices. Autodesk themselves have enjoyed considerable success in the low-cost market with AutoSketch, but until now Generic CADD was their only mid-priced product. AutoCAD LT effectively replaces Generic CADD, and by linking it closely with AutoCAD Release 12, the company hopes to make a breakthrough in this market.

What exactly is CAD? CAD programs are Design and Technical Drawing tools which bring benefits such as speed and ease of change over manual methods. The most important distinction between CAD and other drawing programs is how data is stored. Paint programs, such as Windows Paint, store pictures rather like a sheet of graph-paper with squares filled in. Although a picture portrays lines, circles and arcs, the program doesn’t understand the content. CAD drawings contain collections of geometrical objects such as ‘lines’, ‘circles’ and so on, which are stored to extremely high levels of accuracy – sometimes 14 places of decimals. Because the drawings are Object-Oriented, there’s no link between what’s visible on the screen and the accuracy of the drawing. When a detail of a CAD drawing is magnified, the program re-calculates the drawing so that it’s displayed to the screen’s best abilities.

It’s useful to distinguish between CAD programs and Object-Oriented Art packages such as Corel Draw!. While Art packages concentrate on the end result, CAD programs focus on the subject – the item represented in the document is more important than the document itself. CAD programs make few concessions to beauty, being geared towards the clear and accurate presentation of technical information.

All CAD programs, from budget to professional systems, perform broadly similar functions. Drawings are always built using primitive objects such as lines, circles and arcs. More importantly, all programs provide wide-ranging tools for selecting, manipulating and correcting a drawing’s contents. There are always features which allow details to be magnified, and the view to be ‘panned’ across to other parts of the drawing. Most programs allow drawing elements to be placed on ‘layers’ representing families of data – an architectural example would be to draw walls on one layer, plumbing on another, wiring on another, and so on. Hard Copy output is always provided to plotters as well as printers. Finally, all CAD programs can create libraries of commonly used details, which can then be re-used.

The range of drawing and design tasks which CAD systems can handle is pretty well unlimited – if a design can be drawn on paper, it can be drawn on a CAD system. CAD can be applied to all design disciplines, from Mechanical Engineering, through Architecture to Electronics. Indeed, CAD is now more popular in some industries than manual methods – Printed Circuit Board design is a prime example.

CAD programs can be used in a number of ways. A general-purpose program can be used, with customer symbol libraries & macros evolving naturally over a long period. Alternatively, 3rd-party software can be added to a general-purpose program to provide sophisticated industry-specific features – this approach is already popular with professional programs like AutoCAD, and products are now appearing for budget programs. Finally, there are CAD products which have been designed from the ground up to cater for particular industries.

CAD’s high accuracy opens up possibilities that are not available using manual techniques. Because of inherent inaccuracies, design on drawing boards normally involved calculating all dimensions for every component – a tedious and error-prone business. With CAD however, it’s possible to rely on the software’s inherent precision to read dimensions directly from the design drawing, saving considerable time. When whole phases of the design-process can be skipped, it’s no longer surprising that CAD drawings can be produced typically 70% faster than manual methods.

Just creating paper drawing faster and more neatly is not what CAD is about, because this represents only part of its abilities. For instance, many design methods in regular use today would be impossible without CAD. 3D Modelling and Photo-realistic Rendering, Finite Element structural analysis, and Electronics Design simulation have all become commonplace. CAD drawings should be considered as ‘models’ of complete designs, rather than mere electronic representations of paper drawings. The biggest benefits occur when CAD data is shared – speed and accuracy improve dramatically when re-keying of data can be avoided. Natural ways of sharing CAD data are those where the picture is used directly, such as in Numerically-Controlled (NC) metal-punching systems or in Technical Publishing. Some CAD systems can hide text in drawings and export this information to database systems for Stock Control or Document Management.

Many CAD suppliers have welcomed Windows with open arms, as its enormous popularity has solved the problem of device driver support for displays, pointers and plotters. Before Windows, CAD programs only providing drivers for standard hardware, and suppliers of unusual displays or pointers had to write their own drivers. This was a nightmare for customers, as upgrades to CAD software were frequently delayed while the hardware suppliers wrote suitable drivers. Universal hardware support for Windows is much more important to CAD suppliers than features like multi-tasking.

Unfortunately, CAD makes heavy demands on hardware. Typical professional CAD programs might need a 486DX2 PC with 16Mb RAM, 250Mb hard-disk, and a 17″ or 20″ monitor with a fast graphics card. While the £3,000 needed to purchase a machine of this specification is acceptable when the CAD software also costs £3,000, customers for lower-cost CAD simply want to install the program on their existing PC, with the minimum of additional expenditure. Thankfully, many budget and mid-priced CAD programs perform adequately on standard Windows PCs (386 with 4Mb RAM, 100Mb hard-disk and VGA graphics), although some programs insist on the addition of a Maths Co-Processor. As with many modern Windows applications, CAD performance improves dramatically with extra RAM and faster graphics cards.

The markets for both professional programs (more than £2,000) and budget programs (less than £200) are clearly-defined and well-established, with a wide range of products in each price-band. However, the mid-priced market has until now been strangely subdued, with programs in this field never enjoying the high profile of those in the other price-sectors. This is surprising given the potential size of the market for first-time CAD users and existing CAD sites. Autodesk are clearly hoping to change this with AutoCAD LT.

When considering CAD on PCs, the product that everyone thinks of first is AutoCAD. Originally released over 10 years ago, it was the first professional-standard CAD program for the PC. AutoCAD has gone on to dominate its field by a wide margin, with about 70% of the PC CAD market. Over the years it has evolved from 2D draughting to 3D Surface Modelling with options such as Photo-Realistic Rendering, Solid Modelling, and direct links to SQL Databases. AutoCAD has always been available for a wide range of platforms. Recent versions have supported the PC (MS-DOS, Windows and OS/2), Macintosh, and UNIX workstations (Sun, Silicon Graphics and Hewlett-Packard among others) – older versions even catered for such noble failures as the Apricot and IBM RT.

Many factors contribute to AutoCAD’s dominance, but perhaps the most important is the product’s open architecture. AutoCAD has always provided an unusually wide range of features to permit customising, from simple macros to specialist programs written in high-level languages such as C or AutoLISP (AutoCAD’s internal programming language). The program’s User Interface can also be modified almost beyond recognition – menu items, dialogue-boxes & icons can all be changed. AutoCAD Release 12’s programmability has allowed it to become a ‘CAD construction-kit’ with which to create bespoke CAD applications for specialist markets.

Unfortunately, such sophistication isn’t cheap – £2,800 for AutoCAD Release 12 is a serious commitment to CAD, and there’s been a need for a lower-cost alternative for some time. Although open architecture and 3D are undoubtedly important, it’s unclear what proportion of existing AutoCAD Release 12 customers push the product to its limits. Many users need AutoCAD for compatibility, but only use 2D, never customise the program, and can’t afford a powerful PC – what they need is a slimmed-down version of AutoCAD at a lower price. Does AutoCAD LT contain the right blend of features?

The smallest machine on which AutoCAD LT runs is a standard Windows 3.1 PC, with a Maths Co-Processor. However, more memory is recommended, and the program demands a large chunk of hard-disk space – 8Mb for the program and support-files, and a permanent swap-file of 2 to 4 times physical RAM, or 64Mb for a machine with 16Mb RAM.

At its heart, AutoCAD is a command-based program, with actions executed by typing English-like words at the prompt. A fully-fledged graphical user interface (Windows 3.1-based for AutoCAD LT) sits on top of the command-driven core – a button-press or menu-pick places the appropriate text on the prompt-line, as though it had been entered at the keyboard. This approach helps AutoCAD to give its users considerable flexibility regarding how they operate the program – new users can drive it through the pull-down menus and dialogue-boxes, while more experienced operators can use a mixture of menus and the keyboard. All the definitions for menus, icons and dialogue-boxes can be customised easily.

When AutoCAD LT starts up, a conventional Windows screen appears, containing a main work area, toolbar and cascading menus along the top, and a separate toolbox. The shape and position of the toolbox can be changed – in its floating form it includes context-sensitive Help in its banner. A command-prompt sits at the bottom of the screen and acts as a message-area for program requests or user information. The interface is almost identical to AutoCAD Release 12 for Windows.

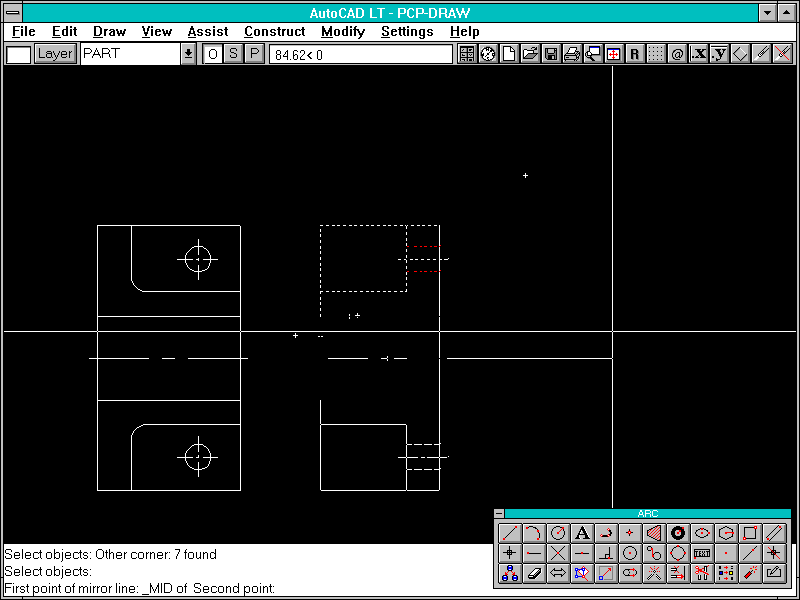

The ease with which drawings can be edited over and over again is one of CAD’s major benefits, and the design of drawing-tools are of paramount importance to a program’s effectiveness. Drawings in AutoCAD LT are created using ‘entities’ such as Lines, Circles and Arcs, which are drawn at full size on an infinite plane. Once a drawing is completed, it is scaled up or down to fit standard paper-sizes by the plotting routine. AutoCAD LT is predominantly a 2D program, although it contains just a few 3D tools for compatibility with AutoCAD Release 12.

The contents of a drawing can be manipulated using either command- or ‘Grip’-based editing tools. Command-based editing can operate in either ‘Verb-Noun’ or ‘Noun-Verb’ mode. With ‘Verb-Noun’ editing the action (such as ‘Move’) is chosen first, followed by the objects. ‘Noun-Verb’ editing, however, expects the objects to be selected before the editing command is chosen – this is Windows’ method, and can be seen in many other programs. ‘Grips’ are a variation of the ‘Noun-Verb’ approach. When the objects are selected, small markers or Grips appear on the objects, which can be dragged to new positions. The precise effect of moving a Grip depends on the type of object – the Grip on the end of a line will alter its length, while that on the end of an arc will change its radius and centre.

AutoCAD LT contains a number of features which help users to draw and edit their drawings precisely, such as forcing the cursor onto nodes on a grid, or ensuring that lines or displacements are exactly orthogonal (horizontal or vertical). Of greater importance are Object Snaps, which lock the cursor on to geometrical features such as line-ends or circle centres. One particularly useful feature of AutoCAD LT is that the user does not have to decide in advance how a point’s position is to be entered – a point can be defined at will by a mouse-click, menu-pick or by entering co-ordinates at the keyboard.

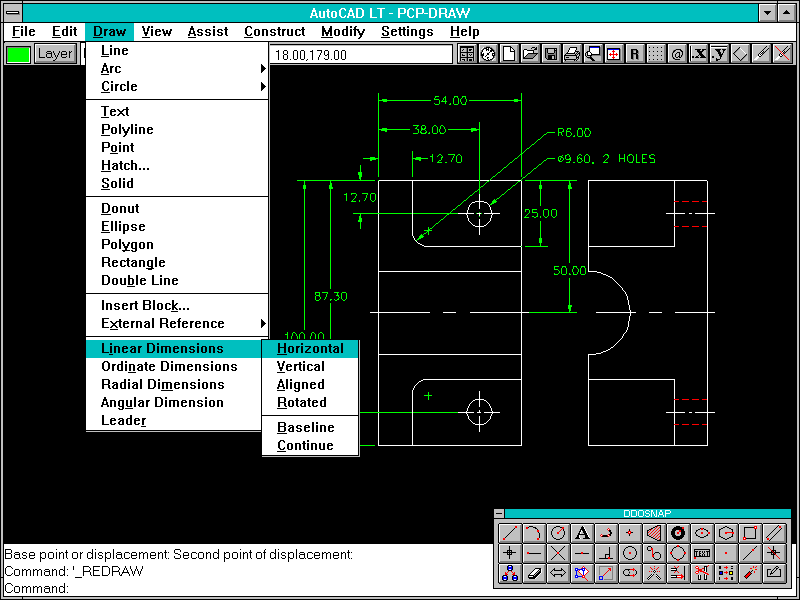

A drawing’s dimensions are its most important feature – if the dimensions are incorrect, the part cannot be made correctly. AutoCAD LT provides an excellent range of dimensioning features, perhaps more than any comparable program. All dimensions are ‘associative’, in that the dimension text changes to reflect any changes in the drawing’s geometry. Every feature in a dimension can be controlled to an extraordinary degree – the multiplier used to calculate a distance, the style of the arrow-heads, the position of the dimension-text and many more features can all be changed to suit the needs of the designer. With so many variables affecting dimensions, there is the risk that specific dimension configurations might be forgotten – thankfully, groups of dimension settings can be saved as ‘Dimension Styles’ which can be re-used in the future.

As well as standard features to zoom in on details or pan across to another part of the drawing, AutoCAD LT provides an Aerial View window. This shows the entire drawing in miniature, as well as the location of the current main screen view. It uses a software Display List, so that zooms or pans performed in the Aerial View are much faster than normal. The main editing screen can be divided up into a number of ‘Viewports’, each of which behaves like an independent screen – this is useful for working on details at either end of a long drawing.

A problem which is frequently encountered when drawing complex objects is the need to show both a general view, and also magnified details. While it’s possible to re-draw these features to the side of the main view, there is always the risk that one view will be overlooked when the drawing is modified. AutoCAD LT’s answer to this is the concept of Model Space and Paper Space. A design is created in Model Space, and Paper Space is used to project the design onto a sheet of paper. Paper Space is a separate plane which contains both graphics such as dimensions and borders, and viewports showing multiple views of a single model. Changes to the model appear in all the Paper Space viewports at once.

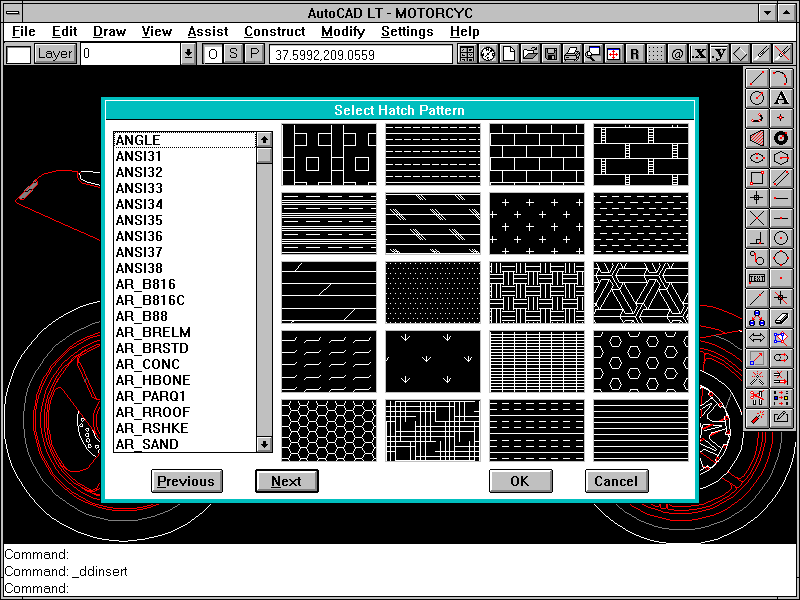

As a drawing’s complexity increases, the information it contains becomes overwhelming. It’s vitally important to control how much information is displayed, and to group certain objects together. Placing features on Layers is a popular method of organising the drawing – any number of Layers can be created within AutoCAD LT, and can be given any meaningful name. Layers can be switched on or off at will to reduce on-screen clutter.

An important feature is the ability to group components together as Blocks, which can be saved to disk and re-used. AutoCAD LT’s Blocks can be either embedded within a drawing, or referenced to another drawing – the current drawing simply contains a pointer to a location on disk. If an externally-referenced Block is changed later, the change will be reflected automatically when the original drawing is reloaded. Any AutoCAD drawing can be imported as a Block into another drawing, making library symbol creation easy.

There’s more to design than drawings – lists and tables are often part of the design package, and CAD drawings need links to such textual information. Special text, called Attributes, can be embedded within AutoCAD LT’s Block definitions. Formatting and prompts are defined in advance, and the block asks for the appropriate information whenever it’s inserted. Attributes can be extracted from drawings and used by spreadsheets or databases – a basic mechanism for generating parts-lists or Bills of Materials.

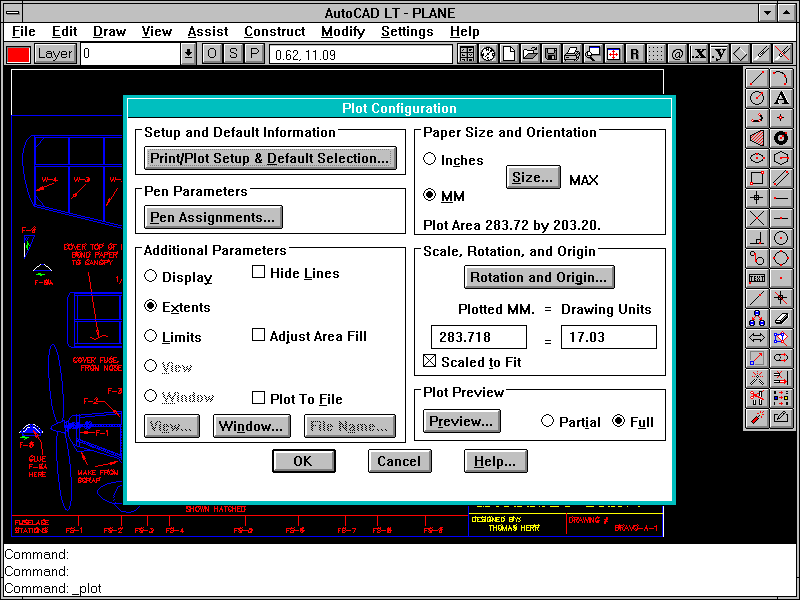

Producing Hard Copy should be one of the most straightforward operations for any CAD system – the only important variables are the paper-size, plot scale and which part of the drawing needs plotting. It’s surprising, therefore, to see how few programs achieve AutoCAD LT’s combination of flexibility and ease of use. AutoCAD LT’s Plot dialogue-box acts as a front-end to the standard Windows Print Manager, and uses the default printer or plotter. The program provides reasonable control over how much of the drawing is printed, and at what scale. Extensive controls are provided for mapping plotter Pen numbers to drawing colours, and setting line-widths for each pen – on monochrome printers the plotting routine uses grey-scales for different colours. There’s even a useful Plot Preview function to confirm that all the settings are correct before paper is wasted.

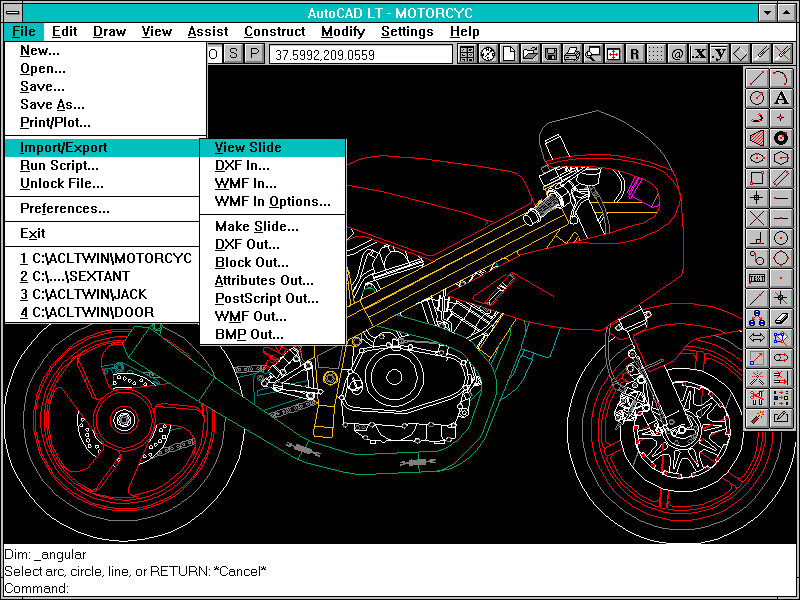

Although seldom obvious to novices, the ease with which a CAD program can share data with other programs is of paramount importance to its long-term success – for self-employed contract designers this can make or break their business. AutoCAD LT is well catered for here – as well as native AutoCAD .DWG drawing-file format, it can import and export DXF and Windows Metafiles. It can also export drawings in Postscript or Windows Bitmap format, which should cater for most eventualities. In particular, AutoCAD LT’s DXF import and export translators are exemplary, being absolutely unbreakable and comprehensively documented, as one would expect from the creators of the DXF standard. Many other DXF translators are by comparison an utter disgrace – despite the clearly-defined structure and programming rules for DXF, some programs accept only a small range of valid DXF entities. This presumes that the recipient of the DXF file can dictate how the source system’s users structure their drawings – a clearly nonsensical situation for small consultancies and self-employed designers working for larger companies.

It’s slimmer than its big brother, but AutoCAD LT still provides many ways for adventurous users to customise the program. The easiest features to use are command-scripts, which can be saved in separate files or written into AutoCAD’s menus. The contents of the menus and dialogue-boxes are completely programmable – it’s also possible to create icon-menus using snapshots of AutoCAD drawings. Although AutoCAD LT doesn’t provide a high-level programming language such as AutoCAD Release 12’s AutoLISP, it does have DIESEL, which is a simple LISP-like language for handling string expressions and intelligent user-interface control – DIESEL code is embedded in the menu file, and with care can produce impressive results.

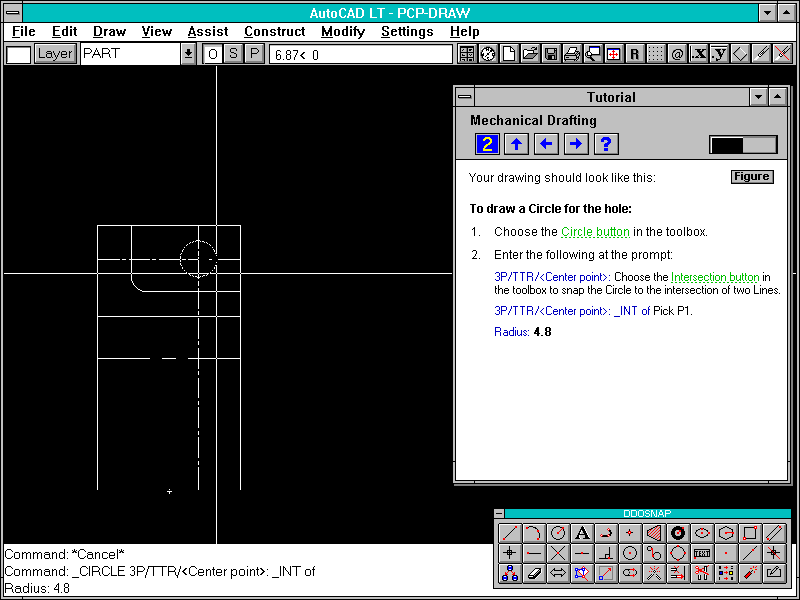

CAD programs contain a vast range of features in comparison with other types of program, and clear documentation is vital to their successful use. AutoCAD LT’s Tutorial contains well-structured step-by-step exercises, based on examples in specific industries such as Architecture and Mechanical Engineering. The User’s Guide contains a thorough discussion of every feature and command, with full details of all support-files, customising facilities and standard libraries. The tone is clear and concise, without skimping on the technical detail. Carefully-chosen screen-shots and examples help to clarify particular points.

Assessing the performance of a CAD program is fraught with difficulty – in practise the absolute speed of a program in benchmark tests is far less important than the ergonomics of the user interface. The one important group of measurable performance parameters is Display Handling – commands such as Redraw, Zoom and Pan are performed dozens of times per session, and weaknesses here will drive the operator to distraction in no time. The overhead imposed on the host PC when running Windows invariably slows display handling, but with AutoCAD LT it’s not enough to cause problems – for the record, it’s about 50% slower than AutoCAD Release 12 for DOS, which is still acceptable.

AutoCAD LT’s interface follows Windows conventions reasonably consistently, with well-structured menus and dialogue-boxes – English-like commands also help operators to understand what’s happening. It’s good to see alternative ways of driving the program – the freedom to choose Noun-Verb syntax instead of Grips, for example, means that everyone will find a method they feel comfortable with, and can change their technique as they learn. Help facilities are good, with comprehensive standard Windows Help, and some useful On-Line Tutorial exercises – however, Autodesk have missed the opportunity to include the excellent Help features seen in AutoSketch for Windows, such as a Smart Cursor or Help Text in the Windows Banner.

AutoCAD LT seems to be aiming at two types of user – the professional on a tight budget who needs a reliable workhorse, and the existing AutoCAD Release 12 user who needs extra seats at lower cost. The balance of features is tipped heavily towards 2D drawing – the few 3D tools are primarily for compatibility with AutoCAD Release 12. It’s first-rate for creating detailed drawings from an initial design, with plentiful facilities for creating geometry, editing, dimensioning, and structuring the drawings’ contents, but advanced features for analysis of the design are absent. If anything, the sheer quantity of features is a potential problem – the Help system and tutorials are useful, but new CAD users will almost inevitably require formal training and time to negotiate the steep learning-curve. An enormous advantage here is the widespread and well-established national training network for AutoCAD Release 12 – support and tuition is available almost everywhere, from special training conducted by AutoCAD dealers to City & Guilds Certificate courses at local technical colleges.

In AutoCAD LT, Autodesk have released a reliable and highly-professional 2D CAD program into a relatively untapped sector of the market. The feature-list is extensive, with all the features a serious user would expect. The interface is almost identical to AutoCAD Release 12 for Windows, and shares with that product a design environment which is workmanlike and unobtrusive – potential customers want a robust and well-proven workhorse at the right price, not gimmicks. When assessing AutoCAD LT, however, the most important factor by far is the name on the box. It’s called AutoCAD, it’s aggressively priced, and Autodesk have another winner on their hands.

Tim Baty

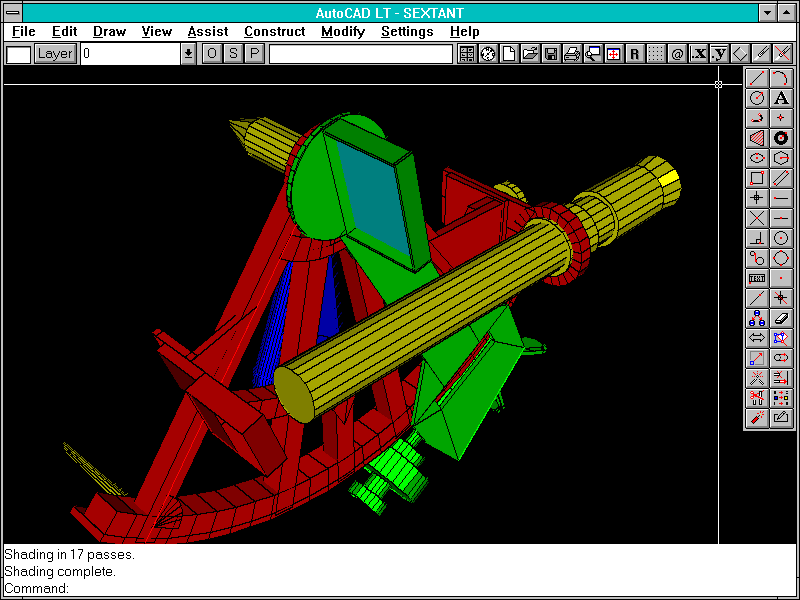

Walkthrough: Creating a design in AutoCAD LT

PC Plus Verdict:

For:

- Huge range of 2D drawing & editing tools

- Comprehensive Dimensioning features

- Excellent Data Exchange facilities

- Widespread training and technical support network

Against:

- Limited 3D

- Steep Learning-Curve

| Score-Card: | |

|---|---|

| Range of features: | * * * * * |

| Ease of Use: | * * * * |

| Documentation: | * * * * |

| Performance: | * * * * |

| Value for money | * * * * |

| PC Plus Value Verdict: | * * * * |

Hardware for CAD

Although Windows’ success has brought higher-quality graphics hardware into the mainstream, CAD still routinely uses items which other users seldom see. Here’s a brief look at typical CAD hardware:

CAD programs are calculation-intensive applications, and Maths Co-processors can speed up such operations dramatically – by a factor of 30 in some programs. At typical prices below £70 for 386’s (and free in 486DX’s), these devices represent a bargain in terms of performance per pound.

Decent Display Systems are now commonplace thanks to Windows, but high resolutions reduce the display speed significantly. Display List drivers improve this by storing the list of instructions sent to the display-card in memory. The list can be re-used when the screen changes without involving the CPU again, giving big speed increases. Although hardware Display-Lists are common in professional graphics cards, some programs now use Display-List techniques internally to improve performance.

Digitisers consist of a pen- or ‘puck’-shaped cursor moved over a flat panel, the cursor’s position being detected as an absolute distance from the panel edge. The ability to detect absolute position allows paper drawings to be ‘digitised’ by tracing over a drawing fixed to the panel. Some programs can also use the tablet surface for command selection.

Plotters provide hard copy on larger paper-sizes than is possible with conventional printers. Pen-plotters are popular and cheap – about £500 for an A3 device. By choosing the right pens, drawings can be created in multiple colours, or with multiple line thicknesses.

AutoCAD LT: The Competition

DesignView V3.0

| Price: | £800 |

| Publisher: | Computervision |

| Contact: | (0203) 417718 |

DesignView is an unconventional alternative to general-purpose CAD programs. Its trump card is Parametrics – CAD’s answer to spreadsheets. Dimensions in conventional programs are passive, simply reflecting the distance between their origin-points. DesignView’s dimensions, however, are active – change the dimension text, and lines or circles change with it. It’s even possible to define relationships between dimensions, using formulae instead of fixed values. It’s ideal for experimenting with designs where some features are constrained by materials behaviour or structural considerations.

Drafix Windows CAD 2.1

| Price: | £395 |

| Publisher: | The Roderick Manhattan Group |

| Contact: | (071) 978 1727 |

Available in different guises for some time, Drafix Windows CAD is a 2D program with some well thought-out features. Entity properties are presented in text boxes near the menu bar, and can be edited directly in text mode. The program also has a strong collection of database links, which are similar in character to AutoCAD’s ‘attributes’.

Caddie for Windows

| Price: | £495 |

| Publisher: | Vector Graphics Systems Ltd. |

| Contact: | (0727) 830551 |

Caddie for Windows is a 2D system, built around a well-designed icon-based interface. The range of tools is more than sufficient to satisfy professional users. Its major advantage is the ability to read and write AutoCAD DWG files directly, rather than having to use DXF for translation.

FastCAD 3D

| Price: | £500 |

| Publisher: | FastCAD Europe Ltd. |

| Contact: | (0923) 240272 |

FastCAD has been working hard to compete with AutoCAD for many years. As its name suggests, the program is written with speed in mind, and in calculation-intensive operations such as 3D hidden-line removal it really flies – other type of operation, though, are not significantly faster than the competition. Unfortunately, it hides a decent collection of 2D and 3D tools behind a crudely-designed and unattractive interface.

CADKEY Drafter 6

| Price: | £995 |

| Publisher: | Merit Computer Solutions |

| Contact: | (0495) 301303 |

Another well-established competitor to AutoCAD, CADKey has a simple, well-designed user interface fronting a thoroughly competent 2D program. While FastCAD scores on high-speed calculations, CADKey performs particularly well with its display handling, boosting speed just where it matters – Zooms, Pans and Redraws are stunningly quick thanks to its internal Display-List driver.