| Publication Details | |

|---|---|

| Publication: | “PC Plus”, UK |

| Issue: | |

| Date: |

| Product Information | |

|---|---|

| Product: | AutoCAD 2000 |

| Price at time of publication: | £3,701 incl. VAT (£3,150 ex. VAT) |

| Supplier: | Autodesk Limited |

| Phone: | 01483-462600 |

| www: | http://www.autodesk.com |

| Fact Panel | |

|---|---|

| Minimum Requirements: | Pentium 133 or better; CD-ROM; 800×600/256-colour VGA display; Windows display adapter; Mouse; 50Mb hard disk space (minimum); 64Mb disk swap space (minimum); Windows NT 4.0, Windows 95 or Windows 98; WHIP browser plug-in; Microsoft Internet Explorer 3.0 or later, or Netscape Navigator 3.0 or later |

| Recommended: | 1024×768 or higher VGA display; OpenGL Version 1.1 with full ICD display adapter; 32Mb RAM + 10Mb additional RAM for each concurrent AutoCAD session |

| Tested on: | Pentium II 333MHz, 128Mb, Win95/IE4 |

Feature Review: AutoCAD 2000

AutoCAD was once the king of the CAD hill, but it’s being squeezed between new-wave budget design programs and traditional high-end programs migrating down to Windows NT. Can AutoCAD 2000 revive the father of PC CAD’s credibility? Tim Baty investigates

AutoCAD is the one Computer-Aided Design (CAD) product which just about everyone has heard of. It dominates the market, having helped Autodesk become the world’s fourth-largest PC software company with over two million copies sold world-wide since its introduction some 17 years ago. This is an impressive achievement for such an expensive and complex product. But just how well does AutoCAD 2000 measure up against its illustrious past?

AutoCAD was the first serious CAD program for personal computers, offering professional design features at a fraction of the cost of programs on technical workstations. It rapidly gained market share thanks to its availability on the IBM PC, although it was also available for many years on other platforms including the Apple Macintosh and various flavours of UNIX. Recent releases have dropped all these platforms in favour of PCs running 32-bit Windows (NT, 95 and now 98), giving Autodesk the opportunity to redesign the program’s internal architecture and improve its speed.

Autodesk have diversified over the years with commodity products like AutoSketch and AutoCAD LT, and professional-grade tools such as the Desktop family for the mechanical engineering, architecture and Geographical Information Systems (GIS) vertical markets. There have been growing signs, however, that the core AutoCAD product is under increasing pressure. It’s a while since we last looked at AutoCAD – Release 13 in Issue 105, to be precise – so to understand the situation we need to look at how the CAD scene has changed since then.

A few years ago most PC CAD programs were general-purpose, with only a few vertical markets such as Printed Circuit Board design benefiting from specialist tools. Users were expected to customise the programs themselves, or purchase add-on modules. In recent years the number of vertical market applications has expanded significantly in all sectors of the market – even the budget sector now includes dedicated programs for garden design and home planning. General-purpose CAD products are still widely available for users with the necessary macro programming skills.

Throughout the CAD market there’s been a major push away from 2D drafting to 3D modelling. More users are now designing in 3D, and manufacturing directly from 3D electronic data – 2D drawings are only prepared when needed to properly document designs, saving huge amounts of time during projects. The most immediate manifestation of this has been customers’ expectations that a good CAD program will contain a full compliment of 3D modelling tools.

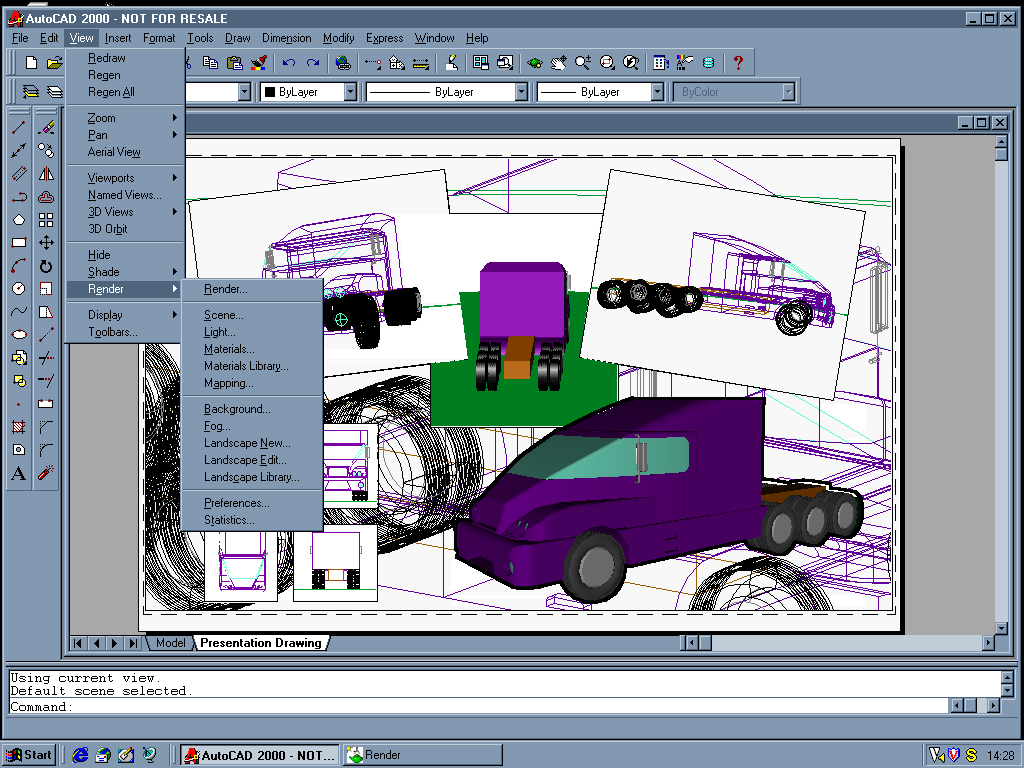

The preferred variety of 3D modelling tools depends largely on the type of customer. Product designers and engineers demand top-quality 3D solid modelling, with advanced editing tools to cope with the complexities of mouldings and castings. Good 2D dimensioning features are also important for post-design documentation. Architects and Geographical Information Systems (GIS) specialists are more interested in 3D surfacing tools for terrain modelling and building visualisation. Photo-realistic rendering and animation tools also help with client presentations.

As with other markets, high-end features have migrated steadily down to lower price-points. Useable 2D drafting & 3D modelling programs can now be found for less than £300, with enough features to appeal to business users. For small cash-strapped businesses, it’s difficult to justify spending ten times this amount on a ‘name’ product.

The professional market has also been busy as established UNIX suppliers port their products down onto Windows NT. Despite huge sales AutoCAD is widely perceived as just a 2D product for PCs – its 3D features simply don’t have the credibility of those offered by SDRC, PTC or Intergraph. Autodesk’s Mechanical Desktop has not yet established itself against I-DEAS and Pro/Engineer in the engineering NT market. The big telecommunications, automotive and aerospace customers are choosing NT versions of I-DEAS or Pro/Engineer in preference to AutoCAD, trapping AutoCAD in the small-to-medium sized business sector. This is precisely the business sector likely to be tempted by budget offerings like TurboCAD, DesignCAD or Autodesk’s own AutoCAD LT.

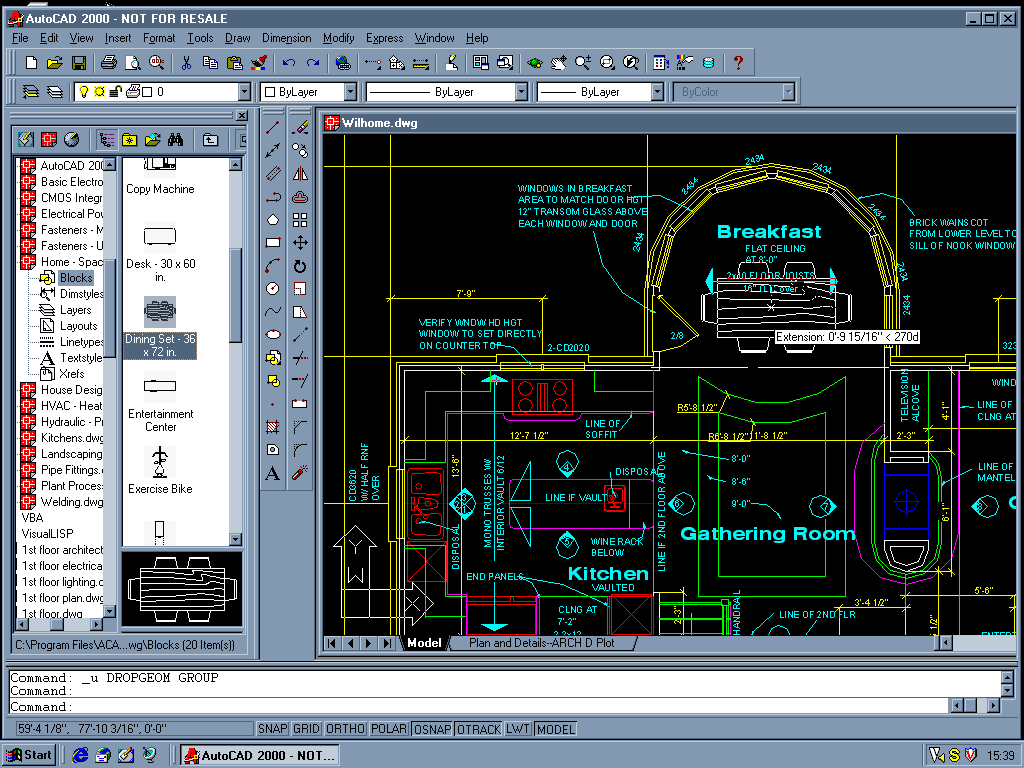

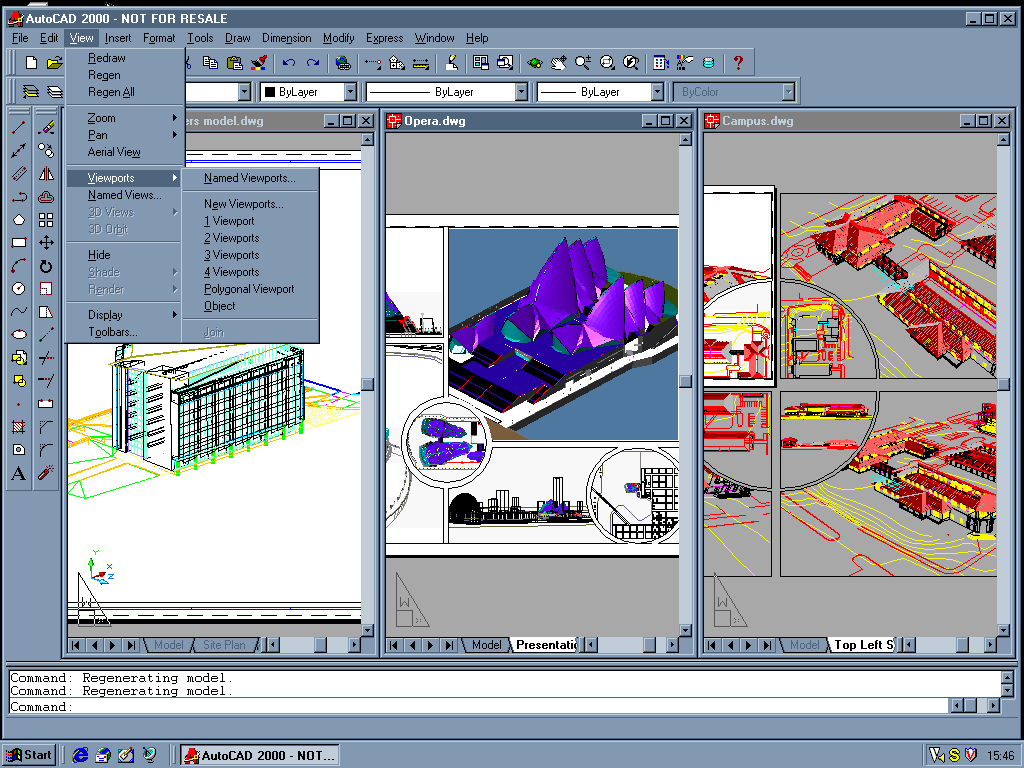

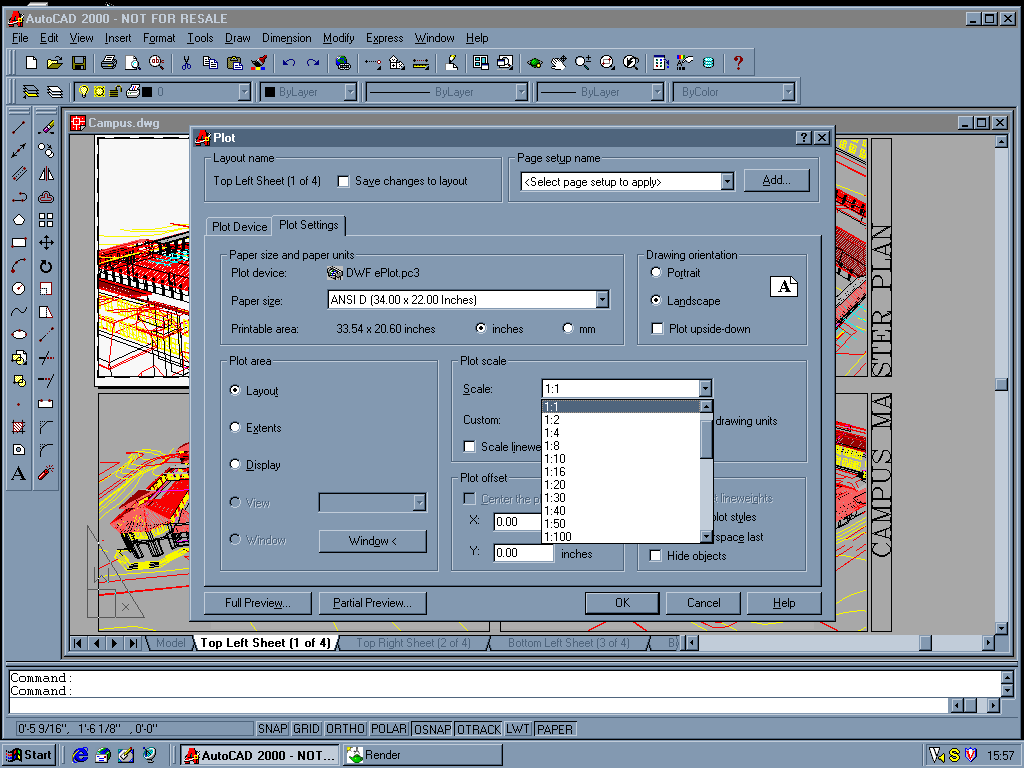

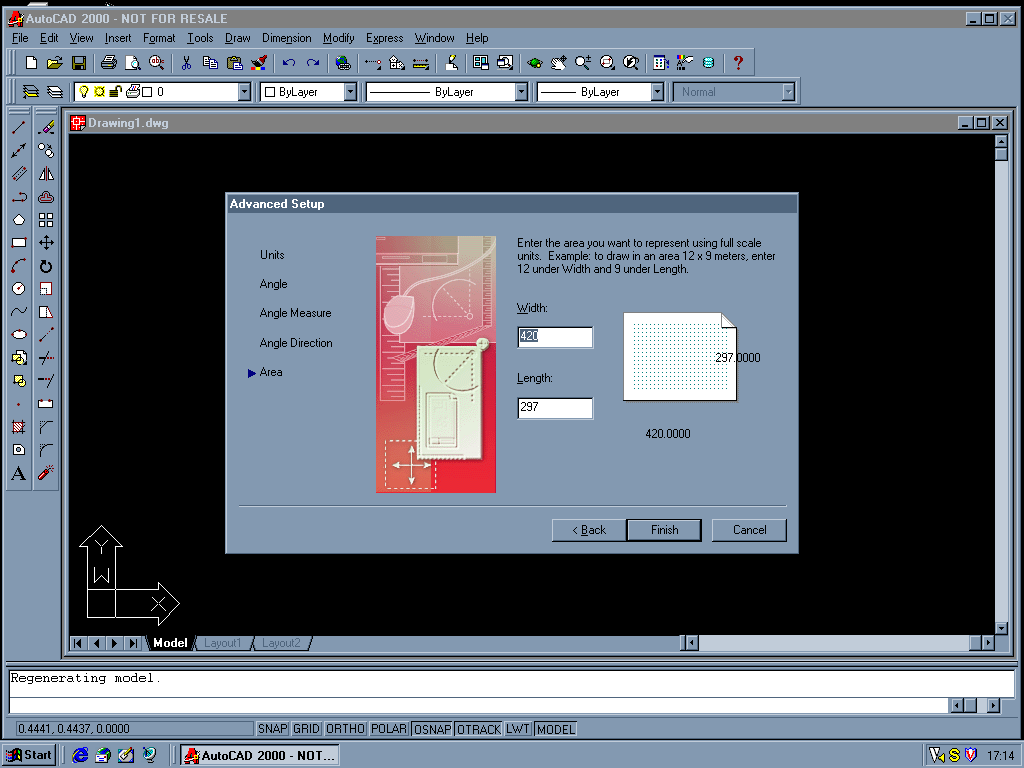

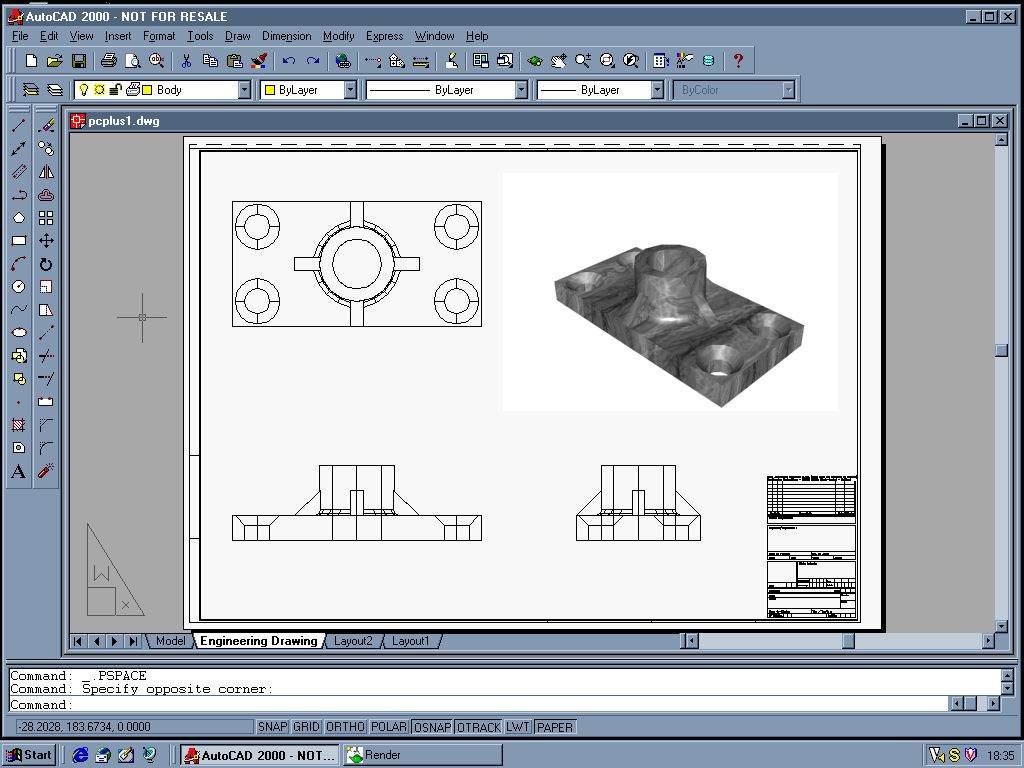

For newcomers to CAD, AutoCAD 2000 is a general-purpose 2D drafting and 3D modelling program. You can mix 2D and 3D objects in the design workspace (Model Space), and can use a separate workspace (Paper Space) for documentation features such as dimensions, annotations and the title-block. Paper Space also contains windows into Model Space, allowing you to view different sides of the same 3D object – the windows can be non-rectangular if necessary. Any changes to your design are visible in all 2D views simultaneously. While this feature is present in most market sectors (including DesignCAD Pro 2000, reviewed in Issue 152), AutoCAD was the first PC CAD program to offer it. Usefully, you can now create multiple Paper-Space layouts, allowing multiple drawing sheets linked to one 3D model.

As you’d expect at this price, AutoCAD 2000 has an exceptionally rich 2D feature-list, with lines, arcs, hatch-patterns, construction-lines, regions and text objects among many other object-types. 2D editing features are equally comprehensive, allowing you to move, copy, rotate, scale and transform objects in every conceivable manner. You can edit objects either by picking the command and then selecting the objects, or selecting the objects and manipulating them with Windows-style handles.

AutoCAD’s dimensioning tools are some of the strongest in the business, with everything from simple linear dimensions to full geometric tolerancing symbols. You can set up dimension features for architectural or engineering drawing practices, and store settings in named Dimension Styles for re-use later. The dimension style dialogue-boxes include a preview, so you can see what effect your changes will have.

There’s a good choice of tools with which to manage the content of your designs. As a design’s complexity increases it’s important to group the data into manageable chunks. Layers are simple but effective – in architecture one might uses one layer for plumbing, another for electricity and so on. AutoCAD also helps you to re-use your work with a full compliment of block management tool, allowing you to build your own symbol libraries. There are also tools for setting up multiple plotter configurations (for line drawings or 3d renderings, for example), and different user profiles to accommodate individual preferences.

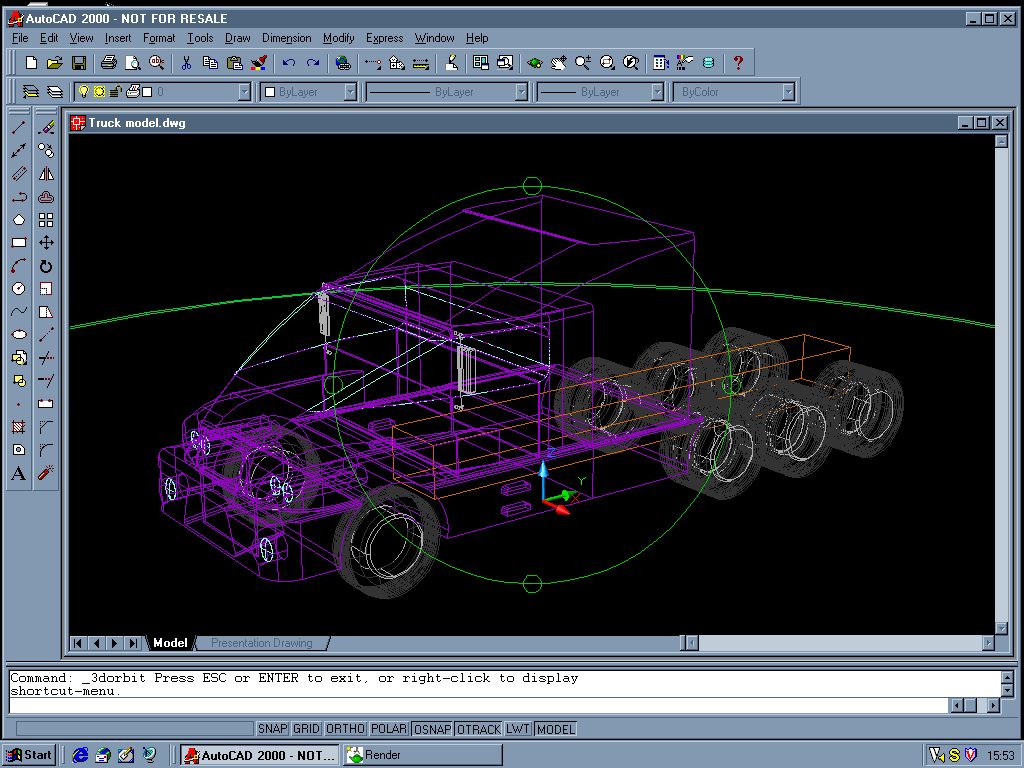

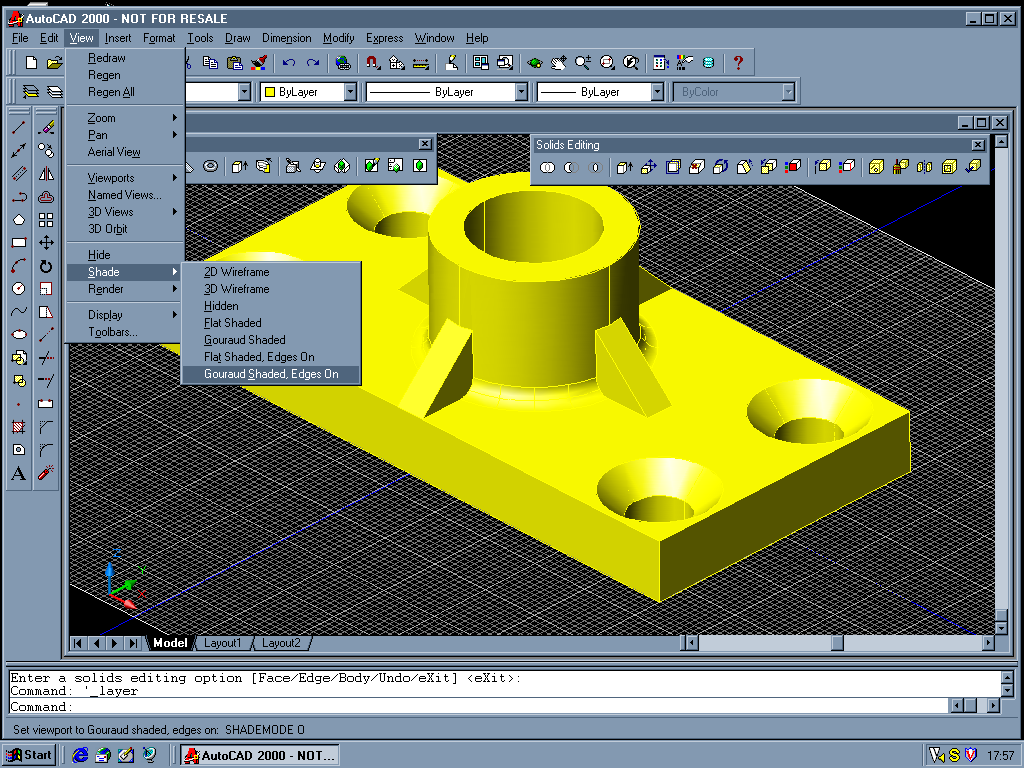

AutoCAD 2000 provides 3D tools for both surfaces and solids, with a comprehensive set of shading and rendering commands. 3D faces and meshes are the most basic form of 3D object. Meshes are infinitely thin, and represent an object’s surface –there’s no concept of ‘inside’ and ‘outside’. It’s extremely difficult to model certain kinds of feature (holes in planes, for example) with surfaces. Nevertheless they’re useful for complex curves or naturalistic features like landscapes.

Solids represent a step up in sophistication, in that they can represent solid material and fresh air. You create solids by combining primitive objects such as cubes and spheres, or extruding 2D profiles. You can also perform complex operations such as hollowing out an object or applying a fillet-radius to edges.

The greatest disappointment in AutoCAD 2000 is the restriction on what you can do with a complex solid once it’s been created. You can move faces and delete them, but you can’t disassemble a solid into its primitives. This is a serious omission, and makes it almost impossible to remove features from an existing solid.

What is particularly frustrating is that AutoCAD is built around Spatial Technology Inc.’s popular ACIS solid modelling engine, which supports advanced features such as history-based editing. A history-list stores a record of every action used to create a solid – draw a cube, draw a sphere, subtract the sphere from the cube, and so on. Users can edit any item in the history-list in isolation. It’s an enormously powerful method of working with 3D solids, and is essential for intensive design work.

It’s difficult to understand why access to the history-list has been disabled in AutoCAD when it’s provided in most other ACIS-based modellers, including TurboCAD Solid Modeler at half the price of AutoCAD. When one sees the history list in Autodesk’s own Mechanical Desktop (which is essentially a heavily-customised version of AutoCAD), it looks as though Autodesk have disabled certain AutoCAD features purely to persuade users to upgrade to Mechanical Desktop. Without some form of history-based solid editing, AutoCAD 2000’s 3D features start to look uncompetitive.

One of the good things about AutoCAD has always been the versatility of its user interface. AutoCAD is essentially a text command-driven program, with a customisable graphical interface sitting on top –you can still control the program by typing commands at the keyboard if you wish. The great advantage of this approach is that it’s been relatively easy for Autodesk to upgrade the interface to include features such as pop-down menus, dialogue-boxes and toolboxes as they became popular. Nowadays the emphasis is on task-oriented toolboxes, users switching on only the toolboxes they need for the task in hand.

AutoCAD’s command-line core has also made it supremely easy to customise, and this version is no exception. As well as simple command-scripts and custom menus, AutoCAD 2000 is provided with a wide range of programming languages for more advanced tasks, including Visual LISP (a Visual Basic-style LISP programming environment), VBA, ActiveX and ObjectARX. Unsurprisingly there’s a huge range of authorised 3rd-party AutoCAD applications and vertical-market add-ons, catering for every possible business CAD activities.

AutoCAD’s new DesignCenter is an Explorer-style window which helps you navigate around your drawings and ‘dig down’ into their content settings for layers, blocks, line-types and such. When you’ve found the particular block or layer setting you want, you can simply drag and drop the setting into the currently open drawing. You can also perform searches on content settings using a Windows-style search dialogue-box. It’s an extremely powerful way of sharing content across designs, and is a welcome addition.

Although it’s essential to be able to share design data with other people, AutoCAD 2000 isn’t the best-endowed program in terms of the number of supported file formats. You can save images in BMP, PCX, Postscript, TGA, TIFF and WMF format, but we’re surprised at the absence of ISO-standard CGM. More significantly, all the supported CAD data exchange formats are either Autodesk’s own (DWG, DXF, DWF and 3D Studio) or Spatial Technology’s (ACIS). IGES and STEP standards are only available as extra-cost add-ons. More positively, AutoCAD links closely to external databases thanks to its SQL connectivity, opening the way for tight integration with sophisticated Product Data Management (PDM) applications.

Autodesk have worked hard to make AutoCAD 2000 fully web-enabled. You can open and save drawings on web servers, and include web XREFs (external library symbols) in your drawings. You can also embed web hyperlinks in your drawings. To minimise download times you can use AutoCAD’s compressed DWF file-format, which can be viewed in any browser with the WHIP plug-in – AutoCAD 2000 provides ePlot, a ‘virtual plotter’ to help you create DWF files easily.

In a review like this it’s impossible to discuss every single new feature in detail – the dozens of items include the usual mixture of ergonomic improvements and extra functions, and are all worthwhile. A welcome break from tradition is that AutoCAD’s minimum hardware requirements appear to have reduced slightly in comparison with recent releases –however, productivity always improves dramatically with fast processors, plenty of RAM and good OpenGL graphics accelerators. The sheer scale of the product is still mind-boggling though, and is seriously intimidating for newcomers – training is essential, both through AutoCAD’s authorised training network and the supplied AutoCAD Learning Assistance training CD.

Any of the major new features such as DesignCenter or the Web integration would be sufficient justification alone for established AutoCAD users to upgrade, but the situation for new customers is far from clear-cut. As a general-purpose CAD customisation environment AutoCAD 2000 is still one of the best products on the market, and is justifiably popular among users in specialised environments and authors of vertical-market applications. The program is also a strong contender in architecture and GIS, where the web features, excellent 2D drafting tools and 3D surfacing all fit well with these environments. Product designers and mechanical engineers however will be unable to tolerate AutoCAD 2000’s limited 3D solid editing tools, and should look elsewhere.

Tim Baty

Walkthrough: Creating a design in AutoCAD 2000

PC Plus Verdict:

For:

- Relatively modest minimum hardware requirements

- DesignCenter

- Huge user-base and support network

- Web connectivity

Against:

- Extremely weak 3D Solids editing tools

| Score-Card | |

|---|---|

| Range of features: | 8 |

| Ease of Use: | 7 |

| Documentation: | 10 |

| Performance: | 8 |

| Value for Money: | 6 |

| PC Plus Value Verdict: | 7 |